on the Sudanese Church of Christ (SCOC) that resulted in the closing of at least one of its churches.

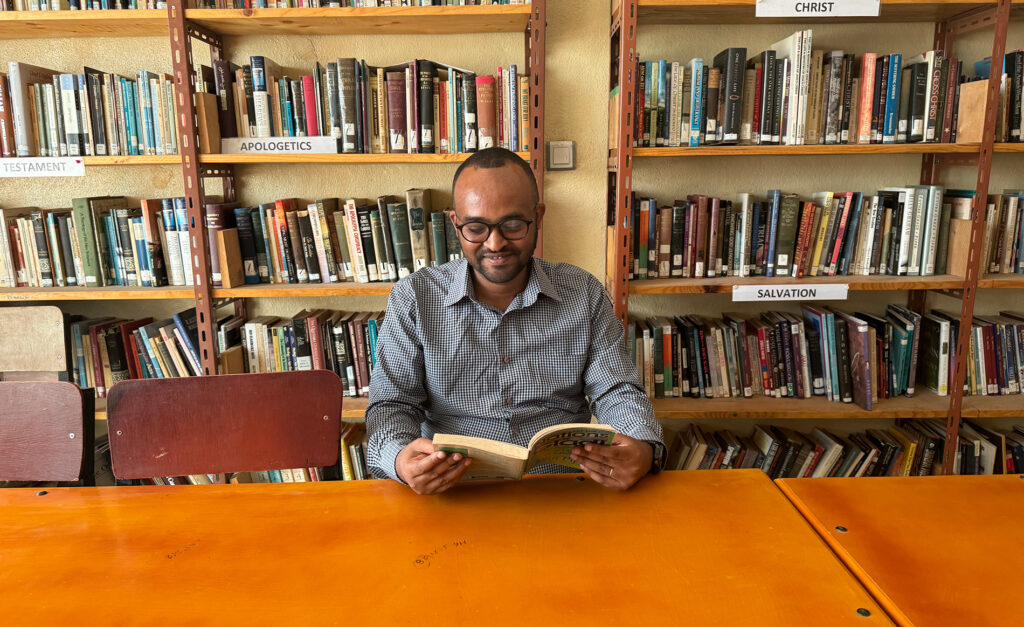

The ministerial order was lauded as the first move in Christian leaders regaining oversight of their churches and properties. The Rev. Yahia Abdelrahim Nalu, head of SPEC, described it as a good step forward.

“Most of the problems that occurred in churches, i.e. the Sudan Presbyterian Evangelical Church, the Sudanese Church of Christ and the Pentecostal churches, were caused by the committees appointed by the government,” Nalu told Morning Star News.

Churches in Sudan became a target of the previous Islamist government shortly after the secession of South Sudan in 2011.

Sudanese Christians and church leaders applauded the ministerial order on social media.

“Congratulations to the church in Sudan, for this is a right decision that is widely accepted in Sudan and outside,” Moris Rafat, a Sudanese Christian, commented in Arabic on his Facebook page.

The committees imposed by the former Ministry of Guidance and Religious Endowment were illegal, according to church leaders.

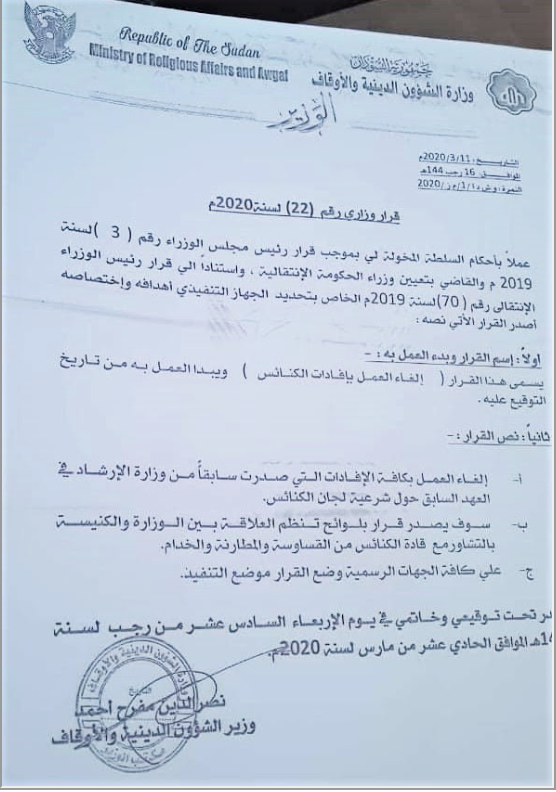

The new order directs officials to implement the decision, stating, “All respective authorities should comply with this order.”

Mufreh said he would issue another order to regulate relations between church leaders and the government but did not include a time frame.

In light of advances in religious freedom since Bashir was ousted in April 2019, the U.S. State Department announced on Dec. 20 that Sudan had been removed from the list of Countries of Particular Concern (CPC) that engage in or tolerate “systematic, ongoing and egregious violations of religious freedom” and was upgraded to a watch list.

Sudan had been designated a CPC by the U.S. State Department since 1999.

Following the secession of South Sudan in 2011, Bashir had vowed to adopt a stricter version of sharia (Islamic law) and recognize only Islamic culture and the Arabic language. Church leaders said Sudanese authorities demolished or confiscated churches and limited Christian literature on the pretext that most Christians have left the country following South Sudan’s secession.

In April 2013 the then-Sudanese Minister of Guidance and Endowments announced that no new licenses would be granted for building new churches in Sudan, citing a decrease in the South Sudanese population. Sudan since 2012 has expelled foreign Christians and bulldozed church buildings. Besides raiding Christian bookstores and arresting Christians, authorities threatened to kill South Sudanese Christians who did not leave or cooperate with them in their effort to find other Christians.

After Bashir was deposed, military leaders initially formed a military council to rule the country, but further demonstrations led them to accept a transitional government of civilians and military figures, with a predominantly civilian government to be democratically elected in three years. Christians were expected to have greater voice under the new administration.

The new government that was sworn in on Sept. 8, 2019 led by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, an economist, is tasked with governing during a transition period of 39 months. It faces the challenges of rooting out longstanding corruption and an Islamist “deep state” rooted in Bashir’s 30 years of power.