“When I was born, I was a slave.”

Jal Masih was born into Pakistan’s modern-day slavery. (“Masih” means “messiah” and is the surname adopted by many Christians in Pakistan.) Jal’s grandfather became enslaved to a brick kiln owner, and his son and grandson inherited a debt they’d never be able to pay off.

Though it’s not legal, around 4 million people labor in indentured servanthood at the 15,000-20,000 brickkilns throughout Pakistan. Many of these slaves are Christians. Every day, these slaves who live at the kilns make bricks to work off an inherited debt that only grows. The kiln owner controls everything in their lives, and often, they are denied education.

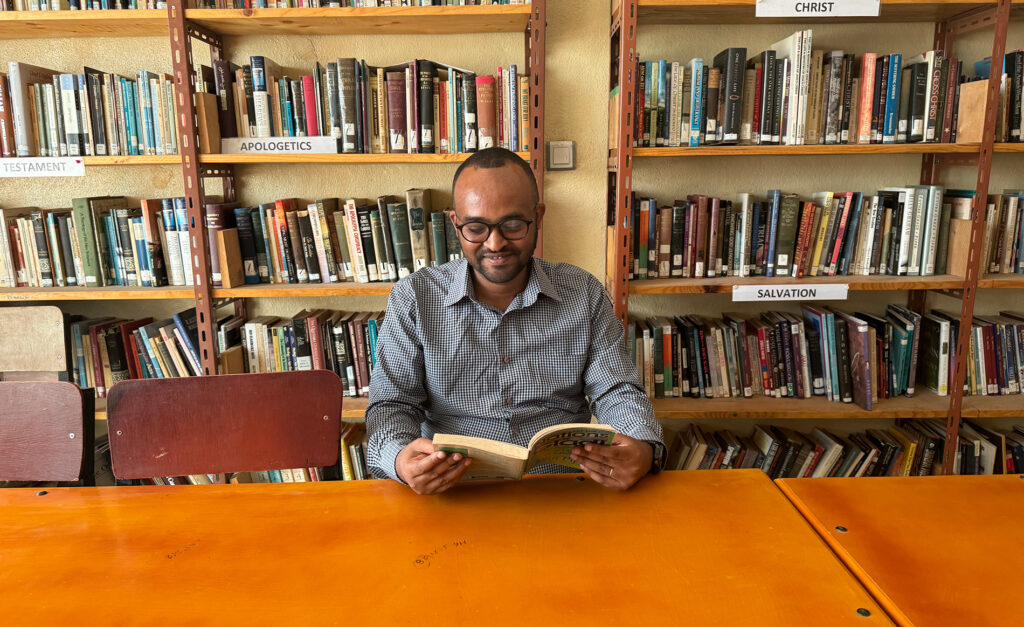

But Jal’s father wanted something different for his son, so each morning, he carried Jal on his bicycle to a small school. “It was a great difficulty, but slowly, slowly I got some education,” said Jal.

Jal thought he had no future outside the brick kiln. His family’s debt was more than 500,000 rupees (around $1,800)– too much for him to pay off. “We were slaves; [we thought] we never could be released from this slavery,” he said.

In his spare time, Jal taught school for the brick kiln children. One day a couple of years ago, someone accused one of the Christian brick kiln slaves of blasphemy. An enraged mob beat the man, and, in the rampage, they also destroyed the school.

But after the riot, an ICR partner came to help. The pastor paid Jal’s debt and got the brick kiln owner to write a certificate of freedom for Jal, his wife, children, and father. “When we were released, we were so happy that God did a miracle,” Jal said.

With help from the ICR partner, Jal and his family reestablished themselves as free people in another town. To date, over 200 families have been freed from slavery by this pastor. Today, Jal runs a small Christian school. “I’m restored, and I’m very satisfied,” he said.

Jal was caught between two major problems facing Pakistani Christians: slavery and the country’s anti-blasphemy laws. These laws make it illegal for anyone to denigrate Islam, and they are often used to punish Christians, though they are used against Muslims, too. There are several Christians in prison right now who have been sentenced to death for blasphemy, while others are serving life sentences.

The accused are almost always innocent, just like in the case of a man named Bashir*. When Bashir was younger, he and another man loved the same woman. To eliminate his rival, Bashir’s Muslim friend asked to borrow his cell phone and then sent offensive messages about Islam from Bashir’s number.

Bashir was arrested, and since 2016, he has been in prison for life. ICR hired a lawyer who is working to free Bashir, but in the meantime, his family is suffering greatly.

Though Christians in Pakistan are at the bottom of the social scale, most people think well of Christians. They know they are moral people who can be trusted. Pastors are respected, which is one reason why ICR partners can approach brick kiln owners and pay ransoms for enslaved people.

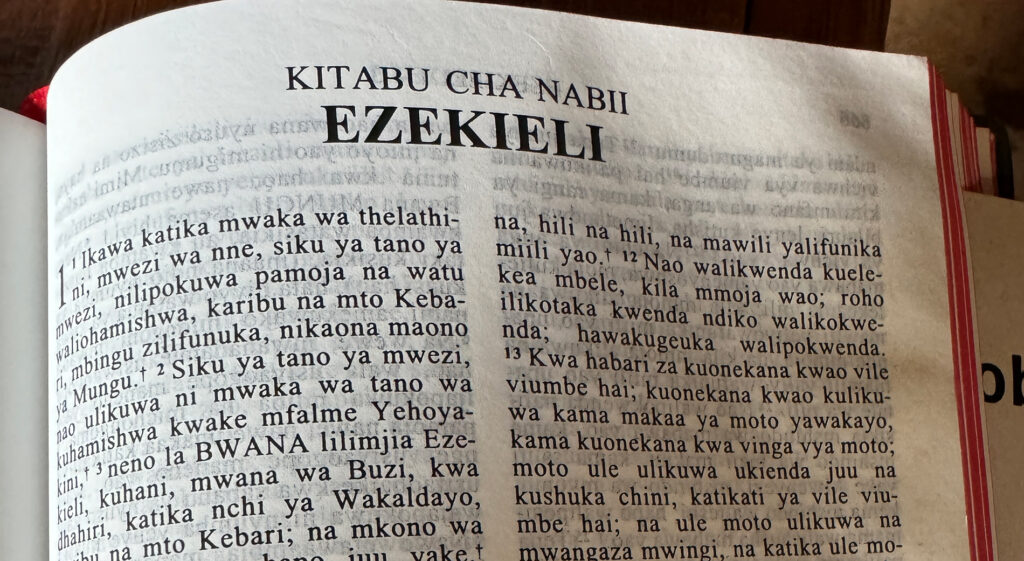

Some ICR partners travel with a Bible on the dashboard of their car. At checkpoints, the police see the Bible and wave the pastors through. Missionaries can openly say they are missionaries, provided they do not evangelize Muslims. And wealthy Pakistanis often prefer to hire Christians as servants, because they trust the Christians not to steal from them. Recently, there have been many examples of these Muslim employers secretly asking for Bibles, and some become secret believers.

“Love is something which Muslim people are always attracted by, because normally in Islam, there is no love, and there is no forgiveness,” an ICR field worker said.

Christians in Pakistan face obstacles at almost every turn: they are prevented from getting in the best schools, they are relegated to poor jobs, and they live at risk of attack, kidnapping, rape, or a blasphemy accusation. Faithful pastors are supporting those who need encouragement and help.

Even in this hostile context, there are believers who want to share Christ at great personal risk.

“I am very convinced that God has called us to share the good news to the lost,” Sidra* told an ICR field worker.

Sidra travels to various cities carefully sharing the gospel. To minimize risk, they never stay overnight. On a recent trip, Sidra walked around a market, chatting with vendors. At the end of each conversation, he offered a gift: a small booklet containing Bible verses and an explanation of the gospel.

On this trip, after he had spoken to several men in the market, his partner called him. “We have to leave now,” he said. The first man Sidra had spoken to was angry. He returned the booklet and started shouting that the Christians were preaching.

The risk of mob violence or arrest is always there, so each time he leaves, Sidra hugs his family members. “I very often had the strange feeling that I don’t know if I will see them again or not,” Sidra said. “I hand over them to the Lord, and tell him, ‘Lord, these are your people and you have brought them in my life, and you can take care of them better thanme, so they are yours.’”

Even though Sidra doesn’t want to lose his family, he chooses to follow what he believes God wants. “The Son of God has come to us here on the earth, and he has commanded us to go to the lost and share the good news,” he said.